From the beginning of the 20th century, Grand Prix racing has been gathering the world’s best drivers. Each year European racing tracks could witness thrilling fights between the most powerful “bolides” — a name given by the French journalists, who never missed a chance to use a turgid phrase or a well-chosen epithet. It was a dream of almost every driver to take a place in the cockpit of such race car. Grand Prix series has become one of the most prestigious competitions in motorsports.

According to the regulations of the pre-war Formula (1934–1937), “the weight of the car without driver, fuel, oil, water or tyres was not allowed to exceed 750 kg. A race car was to have a maximum bodywork width of 850 mm at the driving seat”. Not all teams could comply with these rules. The competition was most intense between France, Italy, and Germany. Well, of course, Mercedes-Benz was one of the strongest rivals.

The roots of the brand go back to the mid-1880s, when the today’s famous engineers Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz invented a car in southwestern Germany. Benz had a repair shop in Mannheim. Gottlieb Daimler and his design partner Wilhelm Maybach were working in Cannstatt. The most interesting part is that we don’t know whether the inventors knew anything about each other at that time. However, later the fate brought them together to create a masterpiece. Here’s how it all began.

In September 1902, Paul Daimler (Gottlieb’s son) registered Mercedes as the trade name. By 1926, DMG (Daimler) merged with Benz & Cie., becoming Daimler-Benz. A three-pointed star design with a laurel wreath wrapped around it became the emblem of the new company and the cars were supplied to the market under the Mercedes-Benz name. Two years later, Ferdinand Porsche left for Steyr Automobile and then in 1934 he found himself in Auto Union. At Daimler-Benz, he was replaced by Hans Nibel, who was also an outstanding engineer. The first eight-cylinder model — the Nürburg 460 — made its debut at October’s Paris Motor Show. This car marked the beginning of the Mercedes’s sports career. Unfortunately, the company’s founders did not live to see that day — both Karl Benz (at the age of 84) and Wilhelm Maybach (at the age of 83) died in 1929. The life of the cars they had created continued in new generations, which never forget to verify their reputation with the help of new records and victories. A year later, Hans Nibel, the designer of successful sports cars fitted with a supercharger, was able to bring the capacity of a Mercedes to 300 horsepower at 3,400 rpm. However, not many drivers could handle a 300-hp monster not equipped with power steering. The names of those who could — Rudolf Caracciola, Manfred von Brauchitsch, and Hans Stuck — became legends half a century later.

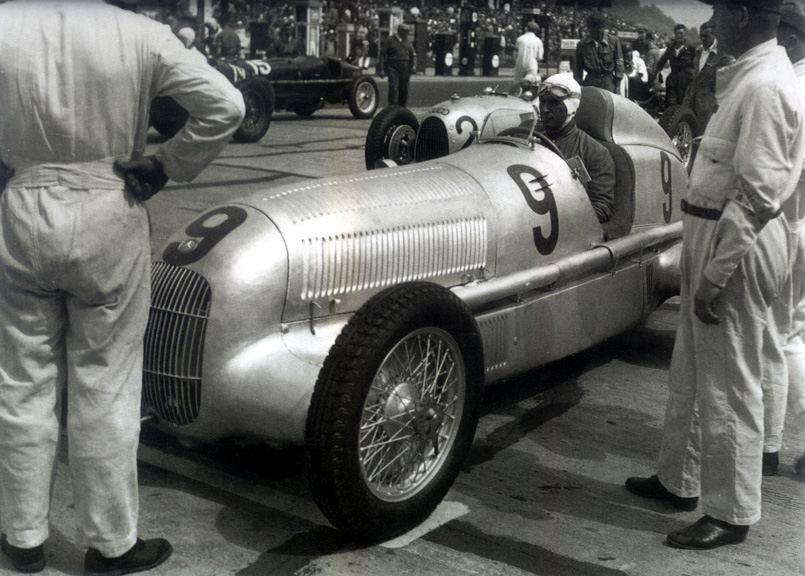

At first, Rudolf Caracciola (inside the sportcar on photo above) was one of the most gifted engineers spotted by Mercedes. However, tightening the screws was not his only talent. In 1931, he became the first non-Italian driver to win the Mille Miglia road race, one of Europe’s major competitions. Caracciola covered the distance of 1,000 miles driving the Mercedes SSKL at an average speed of 140 km/h.

One year later, Manfred von Brauchitsch (competing as a private entrant at that time) scored victory piloting his Mercedes-Benz SSKL with a streamlined body at the AVUS track in Berlin, setting a world record of 200 km/h for its class. After that, the driver was invited to join the German racing team.

However, victories don’t come easy. The teams and drivers suffered a sudden twist of fate. In 1934, according to the modified regulations for Grand Prix racing, the total weight of a race car was not allowed to exceed 750 kg. And that was much lower than the weight of Daimler’s cars. Ferdinand Porsche, who was working with Auto Union at that time, introduced his P-Wagen project. Adolf Hitler decided to support both the new company Auto Union, which took over Porsche's concept, and Mercedes-Benz, which had more than a quarter century of experience in major international racing.

The German race car was developed by Hans Nibel together with Porsche, who was working with Auto Union at that time. The sketches and vehicle assembly were kept under tight wraps. The first information about them appeared in late autumn of 1933, when the team from Stuttgart came to Monza to conduct tests. Based on the project developed by Porsche, Daimler’s engineers were able to get more power in spite of reducing the car’s weight and engine size. The engine reduced by half was nevertheless able to produce 300 hp.

On May 27, 1934, a splendid Grand Prix car debuted at the Avusrennen in Berlin. Many of its competitors looked like some creatures from the Mesozoic Era. The name of the car that was supposed to overtake everyone and everywhere was the Mercedes-Benz W25.

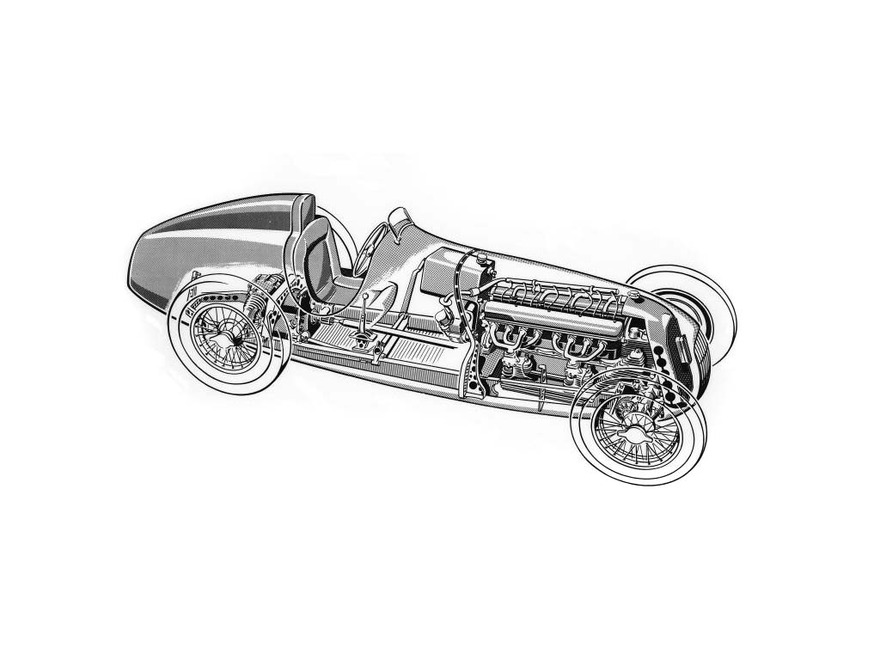

In those years, the streamlined design of German race cars was creating a feeling of tremendous speed and rashness. In comparison with them, the Italian and French cars looked, to put it mildly, rather out of date. And from the technical standpoint also. Mercedes made a significant step forward in comparison with the best models produced by Alfa Romeo and Maserati. Neither Nibel, nor Porsche were setting the goal to create the most powerful race car. Their main objective was to build a car with the best riding performance. For this purpose, they fitted their cars with a stiff tubular frame and an independent suspension on all wheels — Mercedes-Benz had coil suspension, while the Auto Union cars featured a torsion bar suspension on the front and had a transverse leaf spring on the rear axle. The powertrains also delivered outstanding performance — Auto Union’s 16-cylinder V-shaped engine made use of 4.36L of its total displacement to produce 295 hp, while the inline eight-cylinder 3.4-litre mill of Mercedes cars was delivering 280 hp in the beginning of the season. After its displacement was increased to 3.6L, it was able to produce 350 hp.

German cars made a successful debut at the Eifelrennen race held on the south circuit of the Nürburgring. That was where Mercedes-Benz cars started using silver body colour, which became a prominent feature of all race cars from Stuttgart up to our days. When the Mercedes-Benz W25 was put on the scrutineering scales one day prior to the race, it was found that the car’s weight was 751 kg instead of an allowed maximum limit of 750 kg. The team’s racing manager Alfred Neubauer ordered the mechanics to remove all the white paint from the bodywork. Next morning, all Mercedes-Benz cars were showing off their shiny aluminium bodies. During the next scrutineering, the scales recorded the weight of 750 kg. Manfred von Brauchitsch, piloting a Mercedes, scored victory in that race, outperforming Auto Union’s Hans Stuck by 1.5 minutes. The journalists gave the Mercedes cars the “Silver Arrows” nickname straight away.

In 1934, the W25 clinched victories in three more major motorsport competitions: the Coppa Acerbo, the Italian and the Spanish Grand Prix. Mercedes cars were demonstrating excellent road grip on the popular mountain tracks. In spite of all ups and downs, 25-year-old Rudolf Caracciola became European Champion after scoring six victories behind the wheel of the “Silver Arrow” W25.

Starting from that moment and up to the beginning of the World War II, the German teams were the odds-on favourites in all major competitions. Rare victories clinched by other manufacturers, or just Alfa Romeo to be exact, came as a result of fortunate circumstances and the skills of Scuderia Ferrari’s Tazio Nuvolari, known as the Flying Mantuan. Although the mid-engine race cars designed by Ferdinand Porsche were dominating in the first Grand Prix season with the new weight formula, in 1935 the cars from Stuttgart became the leaders on the racing tracks. After Hans Nibel’s death in 1934, Max Sailer, a former Mercedes racing driver, became head of the Design Office and Testing department. Under his supervision, the W25C models were fitted with 4.31-litre engines, increasing their capacity to 455 hp.

The 1935 German Grand Prix brought an unexpected defeat to the German teams. It was Tazio Nuvolari’s moment of glory. By lap 10, Nuvolari, driving an Alfa Romeo P3, had overtaken all his competitors and was already leading the race. During the pit stop, the fuel had to be splashed into the tank of his car from churns due to a broken pressure pump. As a result, Nuvolari joined the race at 5th place. Again, he had to struggle his way through. Tazio was 2nd by the start of the last lap — he was 35 seconds behind leader von Brauchitsch. Then suddenly the fortune smiled upon the Italian driver — Manfred’s car suffered a tyre puncture and Nuvolari became the winner of the German Grand Prix. That was the only victory clinched by Scuderia Ferrari in the 1935 Grand Prix season.

By the 1936 Grand Prix championship, the German cars became even more powerful. The Mercedes-Benz W25E had a 4.74-litre engine tuned to produce 480 hp, while Auto Union cars were powered by a 520-hp engine with the total displacement of 6.01L.

The 1936 season was a complete repetition of the previous year — there was only one Grand Prix race when the German teams were defeated by Scuderia Ferrari’s Tazio Nuvolari. In all other races, the competitors were just watching the duel between the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union cars.

The modified versions of the W25 model were used up to 1937 until their eventual replacement by the Mercedes-Benz W125. Its last modification, the W25E, became one of the most unsuccessful models — its chassis could not cope with the power of the engine, which affected the car’s riding characteristics. Although the V12 mill had gone through all the necessary trials, the car was too heavy for it. The engineers shortened the body in order to reduce the car’s weight, however, that had an even worse impact on the race car’s handling. In spite of all that, Rudolf Caracciola managed to win the Grand Prix de Monaco in the beginning of the season, with that being the only team’s success in 1936.

Mercedes decided to skip the rest of the season in order to concentrate on designing a better model. While driving the race car, a young engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut determined that the W25’s suspension was too stiff, while its chassis was too soft. He made several corrections to the initial sketches and set out to develop a new car for 1937. With the help of the new model W125, Mercedes team secured leadership in Europe’s Grand Prix for the next four years.

Not many people expected that a full change of leaders could happen on the Grand Prix tracks within such a short period of time and that Alfa Romeo, Maserati and Bugatti, who had been dominating for the previous 5 years, would settle for the role of supporting actors, while their places were taken by two German companies — Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union. The German “Silver Arrows” have received deserved recognition and admiration of the audience.